Gadgets

In the driest place on Earth, water hides in plain sight

Located in the rain shadow of the Andes Mountains, the Atacama Desert in northern Chile is one of the driest places on Earth. The cold Humboldt Current from the Pacific Ocean keeps moisture levels low, resulting in minimal rainfall. This extreme landscape, resembling Mars, is home to a few coastal cities and towns where people rely on an underground aquifer for water, which is rapidly depleting due to overuse. Desalination plants are costly and mainly serve mining operations, leaving communities vulnerable to water scarcity.

A potential solution to this water crisis lies in fog harvesting, a simple and sustainable method of collecting moisture from low-lying clouds. A recent study suggests that fog harvesting could provide significant water resources for the growing municipality of Alto Hospicio, supporting thousands of residents who lack access to the formal water distribution system. In addition to drinking water, fog harvesting could also be used for irrigation and agriculture, offering a local source of fresh food.

Fog harvesting offers a potential solution to the water crisis in Alto Hospicio, Chile, by collecting moisture from low-lying clouds. A recent study suggests that fog harvesting could provide a significant water source for the growing community, supporting thousands of residents who lack access to the formal water distribution system. In addition to drinking water, fog harvesting could also be used for irrigation and agriculture, providing a local source of fresh food.

Fog harvesting relies on a simple set-up involving fine plastic mesh panels that collect moisture from the fog. This harvested water provides a renewable resource that can be used for various purposes, unlike the depleting aquifer beneath the Atacama Desert. By capturing moisture from passing fog, communities like Alto Hospicio can access fresh water that would otherwise evaporate in the dry air.

Research has shown that fog harvesting could be a viable water source for Alto Hospicio, with collectors yielding an estimated average of 2.5 liters of water per square meter of mesh during the fog season. By combining observational measurements, satellite imagery, and mathematical modeling, researchers have demonstrated the potential of fog harvesting to address water scarcity in the region.

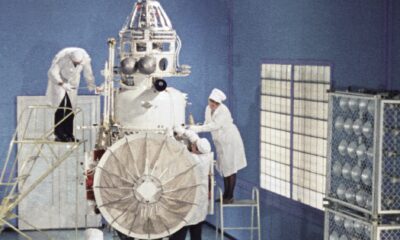

![mesh panels on a desert hill side. The background showcases the ocean in Falda Verde, Chile, where fog harvesting enables the cultivation of lettuce, strawberry, basil, and mint in the desert. Image: Virginia Carter

At this rate, it would take 17,000 square meters of collectors (just over three football fields’ worth) to yield 300,000 liters a week–the same volume of water currently delivered via truck to Alto Hospicio’s informal settlements each week. However, Carter notes this is a conservative estimate, as certain areas to the north of the city have much more fog potential than the average, producing more than 5 liters per meter of mesh per day. If fog collectors were placed strategically, then just 200-300 fog collectors (each encompassing about 20 square meters) could reliably provide hundreds of thousands of liters for at least half the year, she explains. Complementary storage tanks or ponds could stretch the fog water into a year-round resource. “This is kind of a dream. To develop something like that for Alto Hospicio,” Carter says.

If providing drinking water to 10,000+ people proves too big of an initial goal, smaller pilot projects might offer a proof of concept. Carter and her colleagues suggest fog harvesting could also be used to irrigate public parks or provide water to hydroponic farms, with less initial investment. Just 110 square meters of mesh would be needed to fulfill the city’s green space needs. One square meter of fog collection could yield more than 15 kg of leafy greens each year.

Before the dream becomes a reality though, further work is needed. The scientists would like to verify their model estimates with more on-the-ground measurements, to home in on the best locations for fog collectors. Carter says she also hopes to test the quality of the harvested water, and determine what type of treatment would be needed to make it safe for human consumption. Fog can carry exhaust particles, bacteria, and microplastics–like any other natural water source. Yet, even untreated, the water could still have applications in agriculture or mining.

And already the research is advancing. Carter and her colleagues plan to release a publicly accessible, detailed map of fog for all of northern Chile later this year, based on their model. She hopes that local and national government officials take notice. “This study is a very clear example of how scientific knowledge [can] contribute to public decision-making and policies,” she says. “We have a problem: We have no water, and it’s getting worse. But on the other hand, there’s a solution. There’s this water sitting and waiting. We just need a logical way to harvest it.” Please rewrite this sentence.

</p>

</div><!--mvp-content-main-->

<div id=](https://www.popsci.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/LFC-Falda-Verde-Atacama-region-Chile.jpg?strip=all&quality=85)

-

Breaking News2 years ago

Breaking News2 years agoCroatia to reintroduce compulsory military draft as regional tensions soar

-

Destination1 year ago

Destination1 year agoSingapore Airlines CEO set to join board of Air India, BA News, BA

-

Gadgets1 year ago

Gadgets1 year agoSupernatural Season 16 Revival News, Cast, Plot and Release Date

-

Productivity2 years ago

Productivity2 years agoHow Your Contact Center Can Become A Customer Engagement Center

-

Tech News2 years ago

Tech News2 years agoBangladeshi police agents accused of selling citizens’ personal information on Telegram

-

Gadgets10 months ago

Gadgets10 months agoGoogle Pixel 9 Pro vs Samsung Galaxy S25 Ultra: Camera Comparison Review

-

Gaming2 years ago

Gaming2 years agoThe Criterion Collection announces November 2024 releases, Seven Samurai 4K and more

-

Gadgets10 months ago

Gadgets10 months agoFallout Season 2 Potential Release Date, Cast, Plot and News