Gadgets

Can the black hole in the center of our galaxy expand to our solar system?

Black holes, despite being one of the most mysterious cosmic phenomena, have become more understood over time. The first black hole, Cygnus X-1, was discovered in 1971, although the concept had been a mathematical possibility for years.

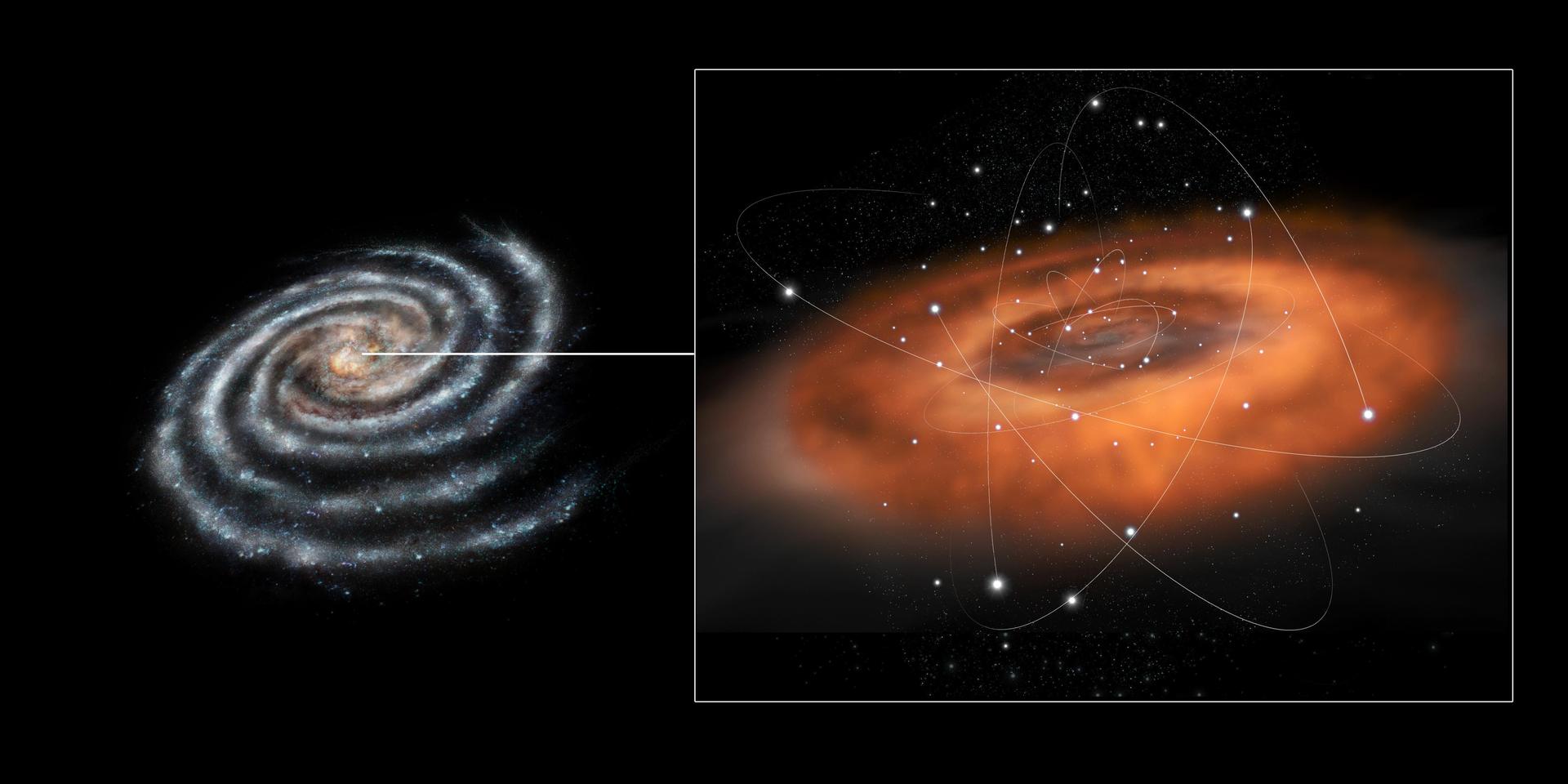

Today, we know that black holes are common in the universe, with one, Sagittarius A*, residing at the center of our Milky Way galaxy. Most galaxies of similar size also have massive black holes at their centers. Sagittarius A* is about 4 million times more massive than the Sun.

Contrary to their name, black holes are not actual holes but extremely dense objects where even light cannot escape their gravitational pull. They are often depicted with a ring of light resembling a donut around them, known as an accretion disk. This disk, made of light and dust, spins rapidly due to the black hole’s rotation.

Contrary to common beliefs, black holes are not voracious eaters that consume everything in their path. If our Sun were replaced by a black hole of similar mass, our solar system would continue orbiting as it does now, albeit at much colder temperatures.

The interior of a black hole remains a mystery, with matter that crosses the Event Horizon undergoing a process known as spaghettification, where it is stretched and squeezed into a noodle-like shape.

NASA explains that black holes are not cosmic vacuum cleaners, and objects can orbit them like any other massive body in space. While their gravity is strong, objects behave similarly to how they do in our own solar system, with only objects too close being at risk of being pulled in.

According to NASA research astronomer Varoujan Gorjan, black holes do not “suck” as commonly believed, and objects can indeed orbit them like any other massive body in space.

Stars orbiting black holes can be torn apart by the immense gravity, resulting in a tidal disruption event where the star is flattened and ripped apart. Some material from the star may be consumed by the black hole, while the remainder continues its orbit.

Black holes can be detected using various imaging methods, including x-ray and ultraviolet scans. Gravitational wave observatories have also observed the merging of black holes, creating ripples in space-time. Scientists are still investigating the origins of the massive black holes found at the centers of galaxies.

Scientists have located black holes by observing fast orbits of stars around invisible objects. These objects are inferred to be black holes due to their gravitational pull on the stars. Cygnus X-1, for example, was identified by its accretion disk formed from material stolen from a neighboring star.

The X-ray signature of the superheated accretion disk was detected.

While there is no immediate threat of our galaxy’s black hole expanding to consume everything, we can monitor the movement of rogue black holes in the universe. The upcoming launch of the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope in 2027 will aid in identifying black holes by observing the distortion of starlight as it passes through a black hole on its way to Earth. This distortion will serve as a clear indication of the presence of a black hole.

This article is a part of Popular Science’s Ask Us Anything series, where we provide answers to a wide range of questions, from the ordinary to the extraordinary. If you have any burning questions, feel free to ask us.

-

Destination6 months ago

Destination6 months agoSingapore Airlines CEO set to join board of Air India, BA News, BA

-

Breaking News8 months ago

Breaking News8 months agoCroatia to reintroduce compulsory military draft as regional tensions soar

-

Tech News10 months ago

Tech News10 months agoBangladeshi police agents accused of selling citizens’ personal information on Telegram

-

Breaking News8 months ago

Breaking News8 months agoBangladesh crisis: Refaat Ahmed sworn in as Bangladesh’s new chief justice

-

Gaming7 months ago

Gaming7 months agoThe Criterion Collection announces November 2024 releases, Seven Samurai 4K and more

-

Toys10 months ago

Toys10 months ago15 of the Best Trike & Tricycles Mums Recommend

-

Toys8 months ago

Toys8 months ago15 Best Magnetic Tile Race Tracks for Kids!

-

Guides & Tips8 months ago

Guides & Tips8 months agoHave Unlimited Korean Food at MANY Unlimited Topokki!